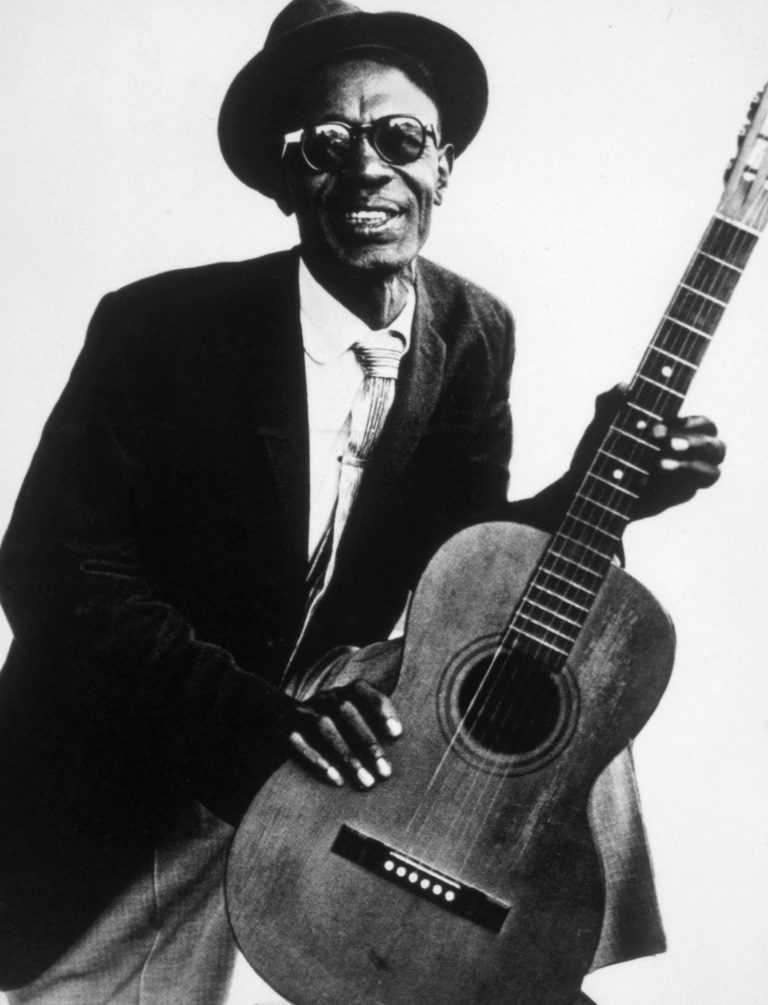

As we approach what would have marked his 110th birthday, it seems a good time to talk about the near-mythic folklore figure of Lightnin’ Hopkins. Born Sam Hopkins on March 12th, 1912 in Centerville, Texas, it wasn’t long before young Sam was immersed in the sounds of the blues. His father was a musician himself, but passed away when Hopkins was incredibly young. The family soon moved to rural Leona, Texas.

After a chance meeting at the age of 8 with bluesman, Blind Lemon Jefferson, at a church picnic in Buffalo, Texas, Sam began learning the blues on a homemade cigar-box guitar from two of his cousins and his two older brothers Joel and John Henry, all four themselves competent guitar-slinging blues musicians.

As Sam became more proficient, so too did his performances alongside Jefferson at informal church gatherings become more frequent. Allegedly, Jefferson never let anyone play alongside him besides the young Hopkins, and his protégé would learn much from his tutor. The melding between church and music would become an incredibly formative part of Hopkins’ musical education, and his mother was soon encouraging him to play organ at her formal church services. However, try as she might, she couldn’t seem to lure Sam away long enough for him to forego his longing for the blues.

As was common for a young, black man in Texas at the time, Hopkins swiftly dropped out of school and began his work on a plantation. In his own laconic words: “I did a little plowin’ – not too much, chopped a li’l cotton, pulled a li’l corn. I did a little of it all.” Outside of work, Hopkins returned to collaborating with one of his cousins, Texas Alexander, and the two spent most of the twenties working, and busking for tips when they could find the time.

The partnership took a brief hiatus, when Hopkins was sent to Houston County Prison Farm in 1930 for an unknown offence. Following his release, he resumed his touring of local picnics, gatherings and juke joints, and he was often permitted to ride public transport for free, providing he played for his fellow passengers.

In 1946, Lola Anne Cullum, a talent scout working for Aladdin Records spotted the two along Houston’s Dowling Street, and asked both Sam and Texas to record, but in a turn which remains unexplained, only Hopkins ventured to Los Angeles in November of that year to cut versions of “Katie Mae Blues” with pianist Wilson “Thunder” Smith. Billing the pair as Thunder And Lightnin’, an lifelong persona was adopted and Sam became Lightnin’ Hopkins.

The track was an immediate hit in the Southwest, and so Aladdin invited the pair back the following year whereby they recorded “Short Haired Women”, which went on to sell around 40,000 copies. Another year later, Hopkins’ track “Baby, Please Don’t Go” sold even double that, with most of those sales around Houston and the rest of the Lone Star State.

At the same time as he was hopping to Los Angeles and cutting records for Aladdin, Hopkins began working with the small, Houston-based company, Goldstar; this would only be the start of a career which would see Hopkins record for over twenty different record labels over his fifty years of performing and recording. Though he was far from prolific when compared to other artists of his time, he was perhaps the most enigmatic, with his recordings appearing in blues, popular, R&B and country charts. Beginning in 1949, the next three years held four more hits for Lightnin’, with “Shotgun Express” reaching number five.

As the hoard of Rock & Rollers began eclipsing most other music forms, Hopkins took a hiatus from recording between 1954 and ’59, although this was interrupted in 1956 with a few smaller records. To an extent, as music went electric and Chess Records’ pioneered plugged-in blues, Lightnin’ Hopkins and his kind were seemingly old-fashioned. Conversely, though, Hopkins remained popular with blues preservationists and the African American community.

However, in 1959, Hopkins and his talents were ‘rediscovered’ by folklore-expert and preservationist Mack McCormick, and The Folkways label revived his career when Sam Charters invited him to record. According to McCormick himself, Hopkins was “the finest sense of the word – a minstrel: a street-singing, improvising songmaker born to the vast tradition of the blues. His music is as personal as a hushed conversation.”

In 1960, as Chuck Berry made way for the Greenwich Village scene, Lightnin’ joined a bill at Carnegie Hall with Joan Baez and Pete Seeger, and was soon on stage in Berkeley, California at the University of California Folk Festival. This period culminated with his appearance on the prestigious CBS special, A Pattern of Words & Music.

As mentioned before, Hopkins never committed all that well to just one label, and for the remainder of the Sixties, he appeared on a number of them. He insisted on recording with a monetary advance, claiming that royalty payments were all-too-unreliable for a musician to make a proper living. According to Richard Havers, Hopkins was also relentlessly efficient, usually needing no more than one take to cut any given track.

In 1967, after playing the prestigious Newport Folk Festival, Lightnin’ became involved with filmmaker Les Blank, featuring in both that year’s The Sun’s Gonna Shine and the follow-up short, The Blues Accordin’ To Lightnin’ Hopkins.

The new decade brought with it new opportunities, and like many of his fellow bluesmen, Hopkins settled down to record The Great Electric Show; this was something of an experimental electric blues album, but it was a setting of unease and something wholly unfamiliar to the primarily acoustic-focussed troubadour. Moreover, despite his dislike of flying, Hopkins took the opportunity to appear in places like Japan and even Britain for the first time, going so far as to perform on several prime-time television shows in the countries which had received his music so well.

The acclaimed Poet-In-Residence for Houston for over 35 years recorded more albums than any other blues musician, releasing more than one per year even as the Eighties rolled around. However, ailing health began to affect Hopkins, and on January 30th, 1982, he passed away aged 69 from oesophageal cancer.

For a man who began life in rural Texas playing church jamborees, the honouring of his memory was astounding by any standard. The New York Times wrote of him: “he was one of the great country blues singers and perhaps the greatest single influence on rock guitar players.” His Gibson J-160e ‘hollowbox’ resides at the Rock Hall of Fame in Cleveland, Ohio, and his trademark Guild at the National Museum of African American History and Culture.

Today, a statue remains of Sam Lightnin’ Hopkins in Crockett, Texas, and he has left a truly indelible mark on all forms of guitar music.

Sources:

Havers, R (2021) Remembering The Legacy Of Ligntin’ Hopkins: The Texas Troubadour. Available At: https://www.udiscovermusic.com/stories/lightnin-hopkins-the-texas-troubadour/ (Accessed 13:00, 17th January 2022)

Unknown (2022) Lightnin’ Hopkins. Available At: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Lightnin%27_Hopkins#Life (Accessed 12:00, 18th January 2022)